"It's about not being afraid to put diamonds and pearls with broken glass and bone," says Robert Ebendorf. The master jeweler's mixed-media philosophy comes from nearly six decades of working with found objects. When you're a self-proclaimed "gleaner," life is an endless treasure hunt. Ebendorf's innovative work has landed in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Now he's form & concept's newest represented artist. We visited Ebendorf's studio to talk about his remarkable career, philosophy of design and day-to-day studio practice.

How did people react to your initial work with found objects in the 1960s?

I was in the forest by myself for quite a while, in a sense. I made such a radical swing from making jewelry with silver and stones—I was never big with gold and diamonds. So when that was happening, I kept thinking “Who’s going to be interested in this work?” I had to contemplate that and make that choice. I stayed with it an pursued it.

The thing is, I have been very blessed. Because I was a teacher at a university, I got a paycheck every month and that helped my studio practice. I could venture into the unknown and uncover my imagination.

Robert Ebendorf, Lucky Fish Necklace, mixed media

You’ve been a teacher for over 50 years. Could you reflect a bit on that experience?

One part of my journey has been mentoring. It’s been a gift to be that involved with young, enthusiastic minds. I was locked into a time zone of 22 years old to 29 years old. Each year I got older, I don’t know about any wiser, but I was locked into that time zone. I realized there was a lot of juice there. A lot of problem solving. Looking back on it, I realize it had a wonderful benefit of being with young people as they creatively try to find their way.

How do you organize your space?

If you look closely at my workbench, I try to make order out of chaos. Now, chaos is all this stuff in front of me. But order is designing, putting colors and textures together. What I call order, you might think doesn’t make any sense. It’s ugly.

There are certain tools I must find and put back on the rack exactly where they belong, so when I’m ready I can go back and it’s there. So I guess there is an order. My beloved wife looks at it, and says, “I don’t see any order.”

You call yourself a “gleaner.” What does that mean to you?

When I’m walking, I’m picking things up and I’m putting things in my fanny-pack. At the seafood restaurant I might gather the claws from the table and bring them home. And in a month, I come back and begin to make a brooch out of it.

Gleaning, finding the discard, I find very enjoyable. When I’m gathering things, I come home, lay them out, clean them, put everything in the right order. It’s my kind of meditative playfulness. There’s something about gleaning that’s been in my DNA since I was a small child.

What sorts of things did you collect when you were growing up in Kansas?

I would go down the alleys with my little wagon. In Kansas, it was a dry state, but I’d go through trash cans and find liquor bottles and go, “Oh, they’re naughty. They drink.” I’d take these things back to my garage. It was a very early sense of gathering and gleaning objects.

I know your gleaning translates into a more holistic life philosophy for you. You speak about the objects you find with really powerful compassion.

I often make reference to the fact that this has been discarded, someone ran over it, it’s been thrown in the dumpster, it’s on the way to the landfill. I enjoy reconstructing it into my world and bringing it out into the universe for another life, another journey. There’s something about putting it back out in another configuration that’s very caring.

Color and composition are foundational to your process. What’s the lesson there?

I just did a workshop with 15 people. A lot of the other workshops at the conference are about technique. Everybody was eager to take a technique home. My group came together and made postcards. I wanted them to take paper, and collage their story together. What I’m trying to share with them is that they can be open to ideas and not be precious. Make mistakes, circle back around.

I was pushing and pulling with them to be more observant and also more loose and open. Everything doesn’t have to be perfect. It comes back to the playfulness.

Robert Ebendorf, Shell Ring, Mixed Media

Do you find yourself puzzling over the lifespan of the objects that you find? Where have these objects traveled before they reach you?

It’s interesting. This piece of copper that I buy in a sheet, I think, “How many lives did this piece of copper have?” It could have been stolen in the sixteenth century— a copper goblet—and then pilfered and taken away, then cut up and melted down, and hammered and maybe made into a tray, or a knife handle. How many different lives? How many wedding rings, or lockets? And now I have it here, and I can hammer it, I can bend it, I can melt it. That’s the magic about that.

There’s a dichotomy in your work, between craft techniques that have been passed down for generations and this radical, avant-garde use of materials.

There is that dichotomy in my work. Maybe that’s why they call me the outlaw. But I do work hard to honor the craft. The workshops were a little different then, but we have the same tools. Fire, melting, hammering. I go to the museums and I look at these pieces that were done in Italy or Nigeria and I think, “These are my brothers and sisters. They are a part of my family.”

When I lecture, I talk about that a lot. It’s something that I honor and feel very joyful about. My grandfather was German. My grandmother was Swiss. They had their own mom-and-pop tailor store.

I remember being 9 years old and watching my grandmother cutting the pattern, getting ready to do button holes. My grandfather pulling out the fabric. Connect the dots. Measuring. Stitching. Fitting. Getting everything perfect. So I do come from a family of makers. Craftsmanship and honoring that—and getting that across to the students—is a biggie.

The places you’ve lived—from North Carolina to Kansas to Norway—have such interesting and diverse craft histories. What are some of the things you learned from journeys?

I left the University of Kansas on a Fulbright to Norway, and then I went back as a Tiffany Grant honoree for another year, and then another as a guest designer. I think that during the Scandinavian design sensibility was coming into the United States in the 1950s. The highly polished silver bowls. Old textiles. Ceramics. Glass blowing.

Living there and going to school under the leadership of those craftsmen really honed me down into the “do it the right way” philosophy. I learned design sensibility and understood the beauty of the craftsmanship. Things being made just perfect.

When I got back, I did high-end commissions for presidents of universities and things for the temple or the church. Highly polished. I started feeling stifled. I was stuck in this one dance. It was very much a result of the Norwegian love affair. That’s when I started to peel the onion and become comfortable. Those were important years. They were the foundation.

When you’re in the process of composing a piece, how do you know it’s finished?

If I was being critical, I’d say I have a problem with editing. I have the tendency to overload. But I like it that way.

That would be my main criticism of my work. More doesn’t always make the piece stronger. Like, do I put pearls here, here, and here. Or just one? I’m constantly struggling with that.

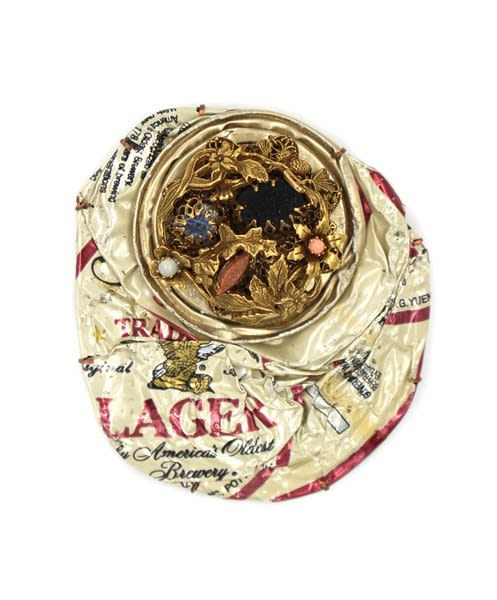

Robert Ebendorf, Lager Brooch, mixed-media

You’re totally shaking up the hierarchy of objects, and the perceived value of different materials.

My work is not about intrinsic value. The value is my sense of design and my language.

When the Victoria & Albert Museum selected a piece of mine that’s on permanent display in their historic jewelry collection, it was nothing more than a paper necklace with decoupaged paper from the street and gold foil. It was not about something having high-end stones and precious metals. It was about celebrating design, and making a personal statement.