Julia Mazal, a Santa Fe, New Mexico native who recently enrolled at Bard College Berlin, is our overseas correspondent. Read on for a dose of "art school confidential," and check back next month for another diary entry from Julia.

One of the first observations I had of Berlin when I was first getting to know the city was that it felt like a giant memorial. It's a city where one is faced with history at every corner. Perhaps those who grew up here don’t notice it as much, but as someone who has just arrived, it is very present. Two of my classes at school have recently addressed the “memorial debate,” the ethics and politics occurring in the art world concerning the best way to address Germany’s past.

I had no idea the amount of theory and scholarly work that was being done in this field. How does Germany even begin to address the gravity of the atrocities that happened in the last century? For years the country has been grappling with the question of memorialization. Many have struggled with the proper way to create monuments that communicate the tragedy of the Holocaust and force the population not to evade personal responsibility.

Key questions many artists and historians deal with concerning the role that art plays in documenting history are:

- What are the intentions of those involved in erecting a monument/memorial?

- How is the historical information being communicated?

- Are the means employed appropriate for the subject matter?

The antiquated effect of the traditional monument has sparked the German memorial debate, leading to the rise of the concept I learned about in class called 'counter-monuments.' They are essentially a more conceptual approach to communicating history, for example, challenging the permanence and figurative representation of a traditional monument.

The first memorial I visited was the memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe, which consists of hundreds of concrete blocks of different heights arranged in a grid pattern in the middle of the city. When you enter the grid and begin to walk towards the center, you can no longer see the surrounding city as the blocks start to tower over you. There are moments when you forget what the blocks are meant to symbolize as you are trying to find your way, but it is incredibly powerful and thought-provoking when you do.

That is what counter-monuments are meant to achieve; a thought-provoking and self-reflective experience, rather than a solely informative one. In my contemporary art history class, we were assigned presentations about the different counter-monuments around Berlin.

I was assigned the Stolpersteine, which are small stumbling blocks laid in the pavement in front of the last known place of residence of the victims of Nazism. The name, place of birth and death, and their fate are engraved on each bronze square. Artists from Cologne, Gunter Demnig laid the first ones in Berlin, and now there are more than 60,000 stones all over Europe.

The Stolpersteine are considered to be counter-monuments because they interrupt your daily urban life as you stumble across them unintentionally most of the time, and so it challenges the idea of intentionally going to visit a memorial/monument. However, these new approaches to addressing history have sparked a multitude of controversies. Many think the Stolpersteine are undignified because you can step all over them without noticing. Many have also criticized the memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe because it is too abstract, so it does not deal directly with the past, and unfortunately, has become vulnerable to ignorant tourists and their selfies.

I think the seemingly never-ending Stolpersteine blocks and the concrete structures of the memorial for the murdered Jews of Europe makes you think of bigger concepts, like the impossibility of representing the extent and gravity of the Holocaust, thus functioning as counter-monuments through their conceptual nature.

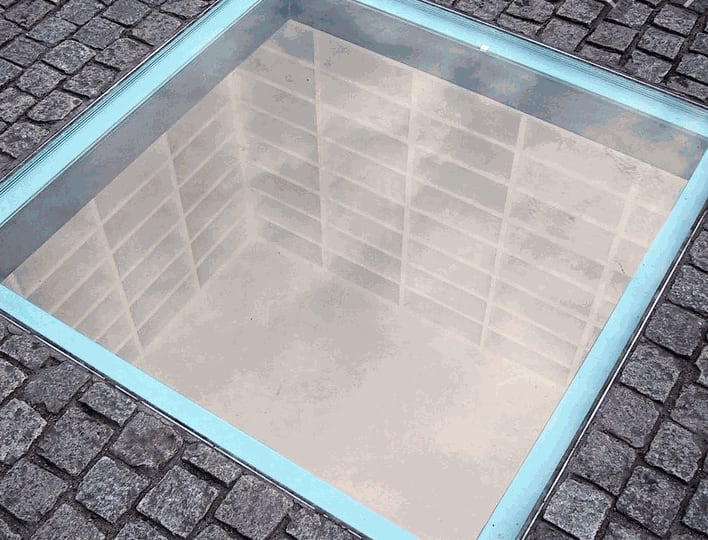

Finally, the last counter-monument I wanted to bring up, which I found interesting is Memorial to May 10, 1933, Nazi Book Burning. The monument is a 5-meter underground room, which is not accessible; the viewer can only see the room from a small glass window embedded in the stones of the ground in front of Humboldt University. It consists of an empty white bookshelf, which I thought was a very clever and powerful way of addressing the book burning. Instead of merely listing the burned books, I realized that it deals with the concept of the absence of them by keeping the bookshelf empty.

Is the debate about artistic representation and memorialization of history taking away from the issue at hand, facing the past atrocities? Should all of the methods and manifestations of commemorating history be treated as individual voices contributing to a collective memory, mourning, and reflection?

I think there should not be a sole method for memorializing, but rather a constant dialogue between different artists, forms, and concepts that are continually evolving, and the counter-monument movement does this very well.

Other counter–monuments in Berlin I highly recommend:

- The Jewish Museum

- Christian Boltanski’s Missing House

- Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism

- Sol Lewitt’s Black Form