"There was so much uncertainty happening in the world with the pandemic, work was uncertain, everything was so uncertain," says Erin Mickelson. The highly-intentional Santa Fe artist surrenders to chance with her new series of print folios incorporating suminagashi, or "floating ink," a marbling technique involving ink, water, care and a little bit of chaos. She continues, "The only thing that felt okay was letting go of that, and suminagashi is one of the only processes that is involved in my practice where I can let go. In a lot of ways, it's weirdly good for me to be forced to let go of some of that control."

As part of her special studio release, Mickelson discusses chaos and control, breaking out of quarantine "purgatory" (even if you can't break quarantine yet), and efforts to reveal the unseen through artwork. Mickelson makes artwork under the imprint Broken Cloud Press, and she also recently inherited the online book arts gallery 23 Sandy. We're featuring 23 Sandy as this month's Partner in Art.

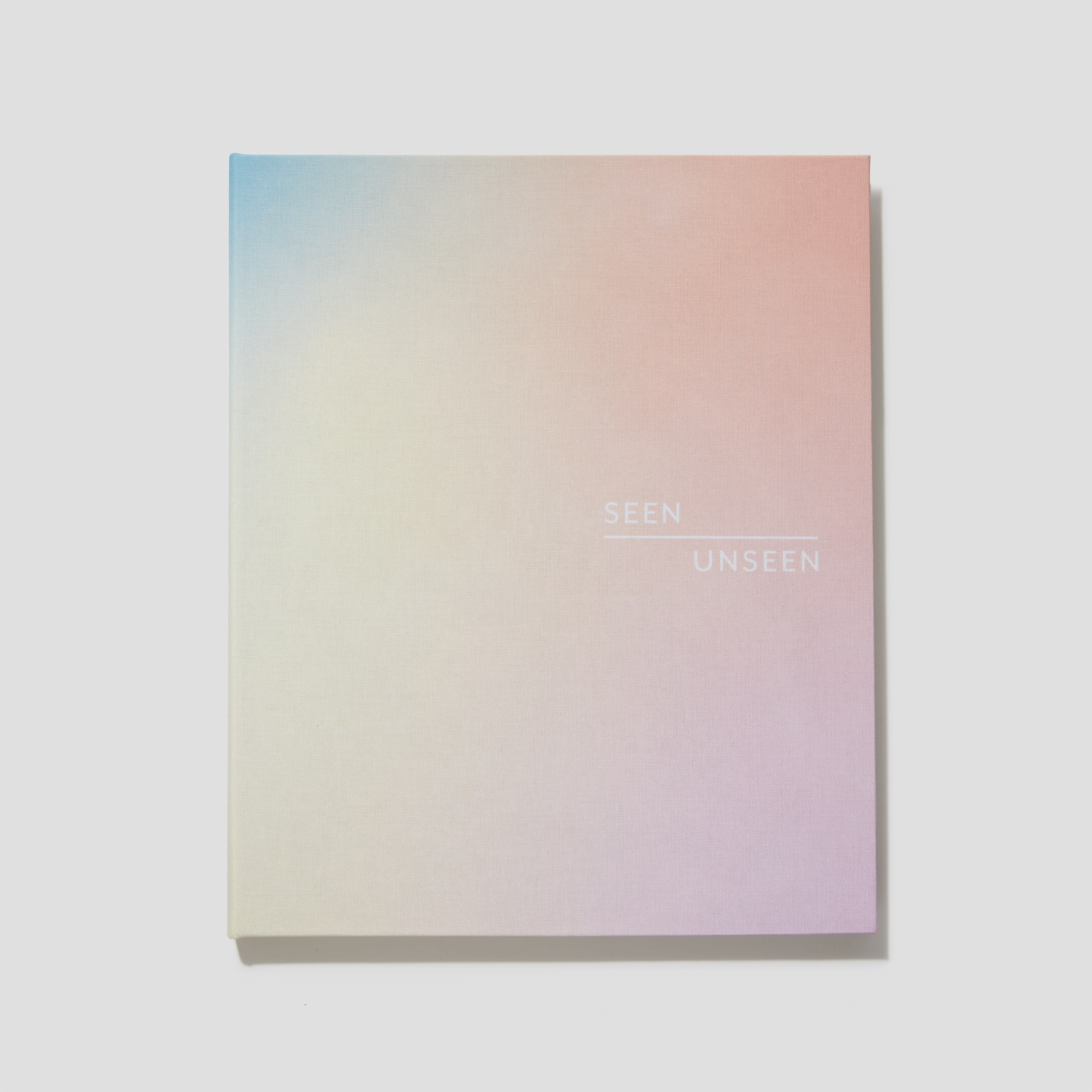

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 1), print & folio (exterior).

Between a group exhibition at form & concept, a residency and a Southwest Contemporary cover story, you had a pretty remarkable 2019.

The Superscript show [at form & concept] was the start of a good amount of momentum for 2019. There was that show, and then Southwest Contemporary reached out, and then I had the residency, which was my first one. It was book art-specific, which was kind of unique.

Things looked very exciting and promising going into 2020. It was set for a solo exhibition at form & concept, and I was planning to spend most of the year making work for that. Then the world fell apart.

Right. How have you been in this strange time, and how is your artistic practice going?

I spent a lot of time in this weird purgatory. It was about a month and a half where I was trying to figure out if my contract work was going to revive, which was sustaining my art practice. For a month and a half, I was at a loss. I did not have a Debra Baxter reaction to the pandemic.

During that time, I was pulling all of these suminagashi prints, over and over, with no intent or purpose. So many suminagashi prints. They felt appropriate. They're a snapshot of this chaotic moment in time, and they're affected by all of these subtle, environmental elements. That's where my brain went.

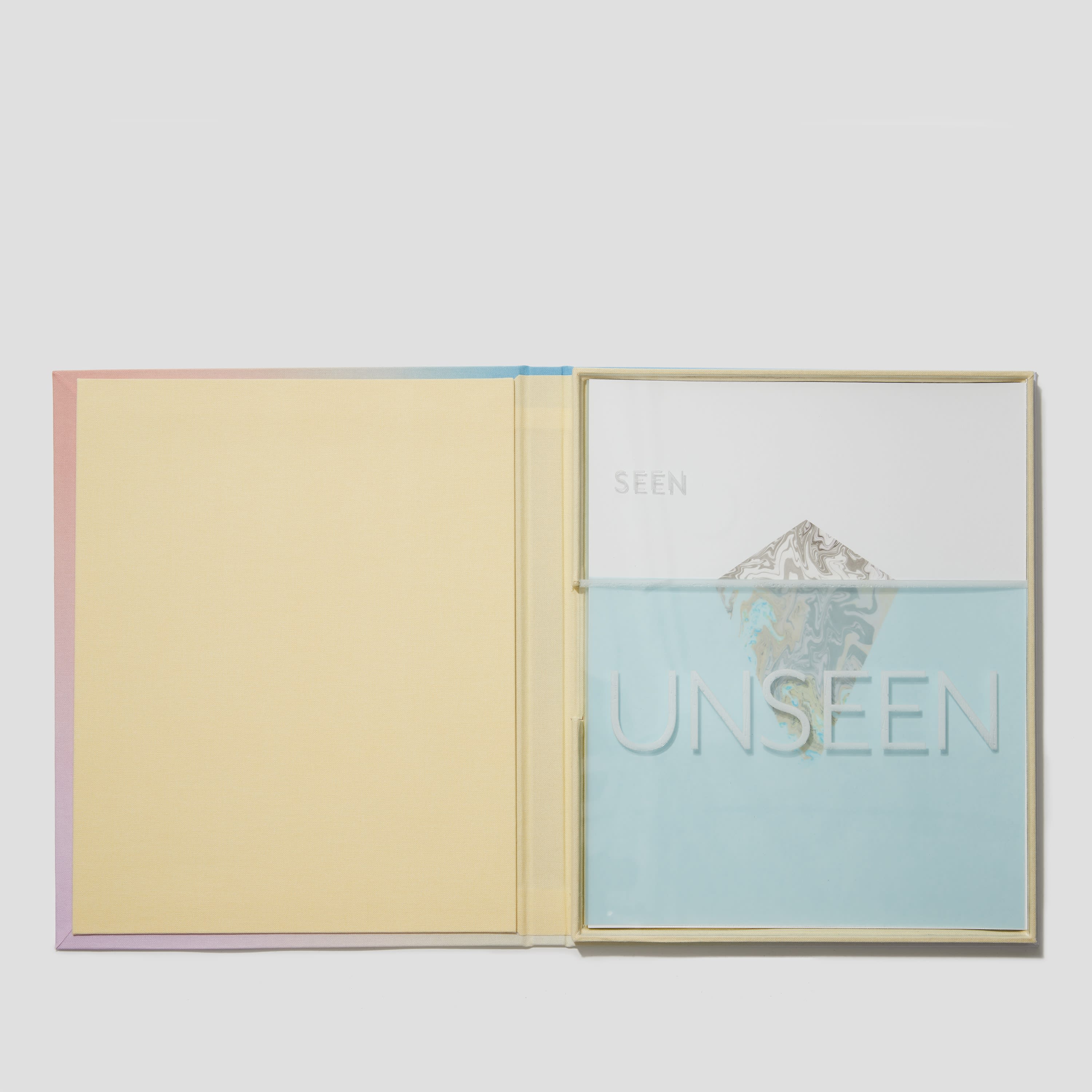

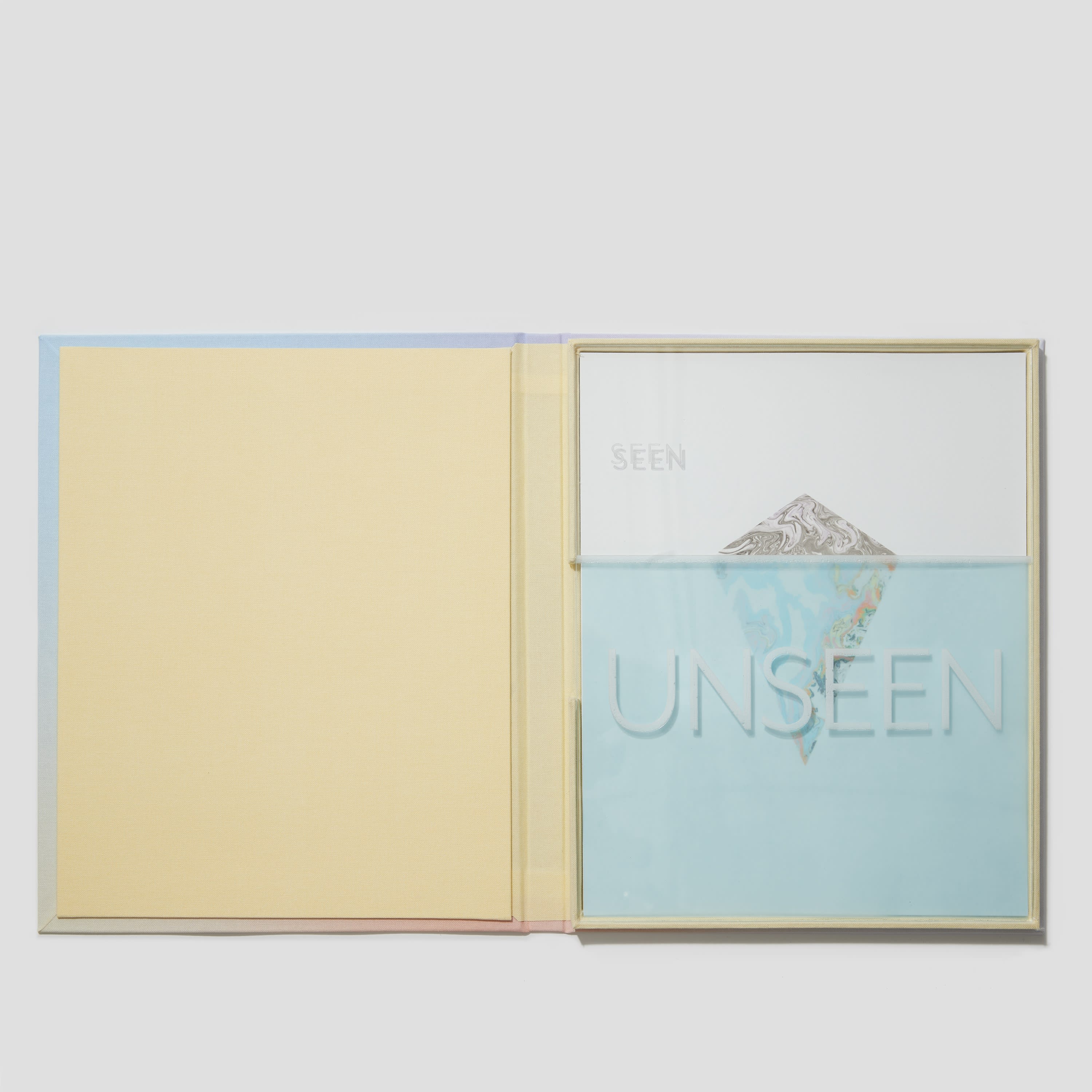

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 1), print & folio (interior).

What a fascinating response to this moment of great upheaval! Is that typical of your artistic process?

In my process, I basically question every choice I'm making and want it to be intentional. I do invite a degree of chaos into my work, but the choice of where that comes in and the reasoning for that coming in, that is very intentional.

I always start with a lot of research for what I'm thinking about, talking about, wanting to say. I want my work to be informed, I want it to be thoughtful. So after the research, it's hard to explain, everything sort of happens on the outside of my vision and kind of coalesces to the center eventually.

So suminagashi, which involves surrendering some level of compositional control to tendrils of ink swirling across water, is actually an outlier for you.

It's very much an outlier. It's the only thing that isn't overthought and second-guessed and overanalyzed. I usually blend constraint and control with chaos in my work. But I typically lean toward the control side. In a lot of ways, it's weirdly good for me to be forced to let go of some of that control. But it doesn't always feel good.

I think that's why I was doing the suminagashi prints in that particular moment. I felt like I had no control of anything. There was so much uncertainty happening in the world with the pandemic, work was uncertain, everything was so uncertain. The only thing that felt okay was letting go of the urge to control, and suminagashi is one of the only processes that is involved in my practice where I can let go.

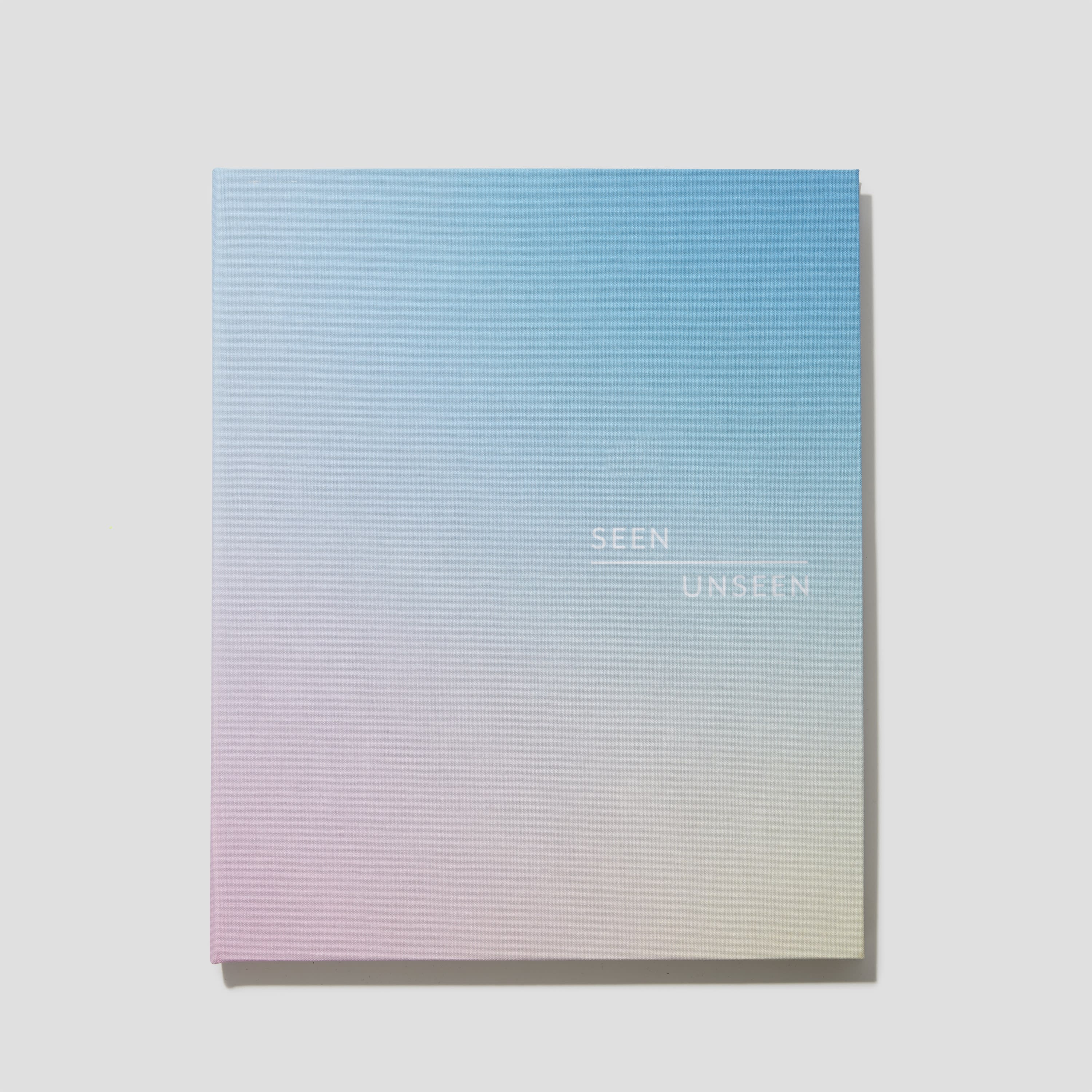

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 2), print & folio (exterior).

How did you emerge from that initial "purgatory" feeling?

I got the word that contract work wasn't coming back, and everything happened with 23 Sandy. That's what I needed to get out of my weird purgatory time period. In addition to figuring out how to revive and learn all these processes that are necessary for 23 Sandy, I was looking at our inventory, looking through old blog posts, remembering old exhibitions, and getting inspired again. Looking at other artists' work, it just made me feel better again. I was able to start being more intentional about creating.

Your solo exhibition at form & concept has leapt from fall 2020 to fall 2021. That's a significantly extended timeline! Could you give us a little sneak peek at what you've been working on so far?

I've been thinking a lot about light and color, and things being difficult to define. That ties in conceptually to the work that I was making for this exhibition. Light and color can be such ethereal things. Think about how hard it is to describe iridescence, transparency or reflection.

This is a little unusual for me, but materials were the first things that started hanging out on the exterior of my vision, the edges. I started doing a lot of material tests using dichroic surfaces, mirrored surfaces.

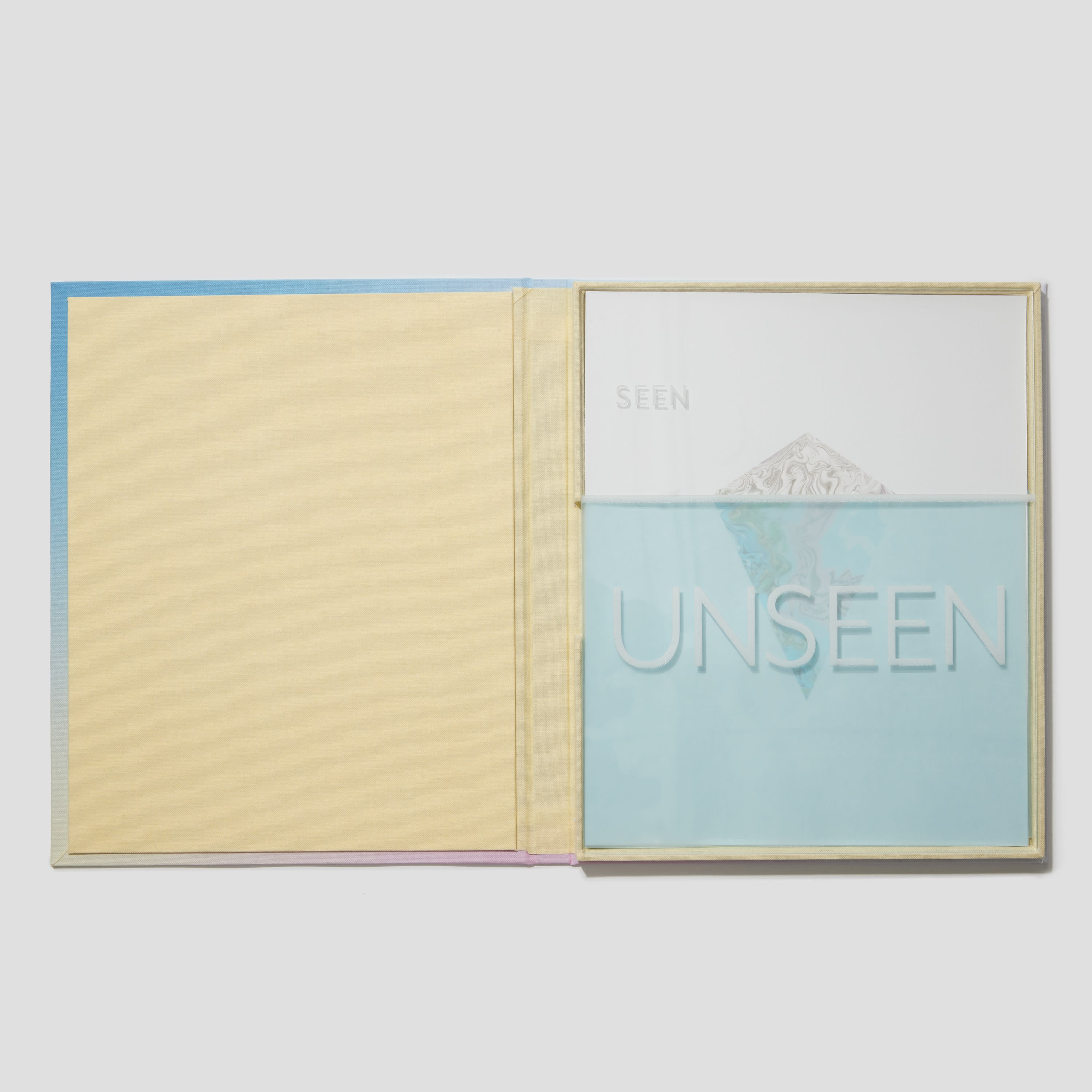

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 2), print & folio (interior).

You work under a personal book art imprint, Broken Cloud Press. What is it about the book as a format that becomes a starting point for so much of your work?

Everything is rooted in the idea of the book, or relates at least. A book is an experience that you move through. I'm always thinking about sequence, and how you would move through a work either visually or physically. The sequencing and the interactive aspects of a work are important to me.

One of the things that has drawn me to books is that you handle them. There's this kinetic relationship that you have with them. With Covid-19 and not being able to touch and interact in that way, needing to keep distance, it's forcing me to think outside of traditional book structure.

How does that idea translate to your solo exhibition, which features many mediums?

I've actually been focusing more on hanging installations. Things that you can experience a bit more sequentially like a book, that you don't necessarily absorb all at once, but that you don't need to touch to interact with. I want to maintain the kinetic aspect of experiencing a book, but it's going to have to be through walking around or between the pieces in order to take them in.

I think of book artists as both fastidious and reclusive. On the other hand, bookmaking is often a highly collaborative process between skilled craftspeople. In light of these contrasting elements, how has life in quarantine been for the book art community?

A lot of people lost access to tools and equipment that were pretty central to their practice, so I know that's been a challenge in the book art world. I'm lucky enough to have my own presses. They're not necessarily as nice and convenient as the press I used to have access to, but at least I can make work. But people have definitely had to pivot to practices that they wouldn't necessarily use.

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 3), print & folio (exterior).

Speaking of 23 Sandy, the online artist book gallery that you inherited from book artist and photographer Laura Russell, how have you leveraged your artistic skills in running the business?

Maybe it's that element of control I was talking about earlier. Laura was incredible in her organization. She had infinite spreadsheets for everything, and her standard operating procedures were tight. She was on top of it, just incredible. A lot of control and organization, and that really helped her be successful.

The backbone of the business is this vast database of book artists and artworks. I'm still learning that, and it's pretty overwhelming. I guess that is probably it, my tendency towards thinking through every part of the process. Having a reason for everything.

Finally, tell me about the artworks you're debuting for this studio release.

Early on in the pandemic, when time felt like it was moving especially strangely, I was walking on the river trail. There was this kind of poignant, heartfelt, comic-y art thing made by a second grade teacher talking about how, "If you think this is bad now, think about what's coming with climate change; we need to work to make things better." That made me think about glaciers and icebergs. Time was on my mind. How things can change in an instant, or not for over centuries. I was considering these long, slow processes, like how long it takes a glacier to melt, and how opposite these suminagashi prints are, this ink floating around and shifting on the surface of a small pool of water.

I was also thinking about things that are visible to us and things that we cannot see, like viruses, the invisible effects of climate change, biases built into systems. I think that collectively, we're starting to wake up to some of that with the dire state of the world and then the George Floyd protests. Racism and oppression have been built into our country since it was founded, and so many people just hadn't been able to see that until the protests happened. The series is about things that are seen and things that are unseen, and how we see really very little.

How did that crystallize-pun intended-into these gorgeous print folios?

I pulled some suminagashi prints on kozo paper that mainly just used black ink, and some that were the colors of glaciers. Then because I have to constrain everything, I cut them into these little minimalist iceberg shapes and used them to make chine-colle prints. There is the "tip of the iceberg"-it's a smaller triangle from a mostly black and white suminagashi print-and then the bottom of the iceberg shape is a larger triangle from a color print.

They're held in a folio, so the print sits on the bottom, and there's a sheet of semitransparent blue vellum that sits on top of it and cuts off where the two triangles meet. So it's concealing the bottom of the iceberg, and you have to physically remove that barrier in order to view the entire print. There's a laser-etched acrylic overlay that sits above the print and vellum, it looks icy and casts subtle shadows on the print.

Erin Mickelson, Seen // Unseen (Edition 3), print & folio (interior).

I think revealing the unseen is such an important practice right now.

I think most people are thinking about that right now, just considering what is unseen, considering that there is a lot happening in the world and in individual lives that is not visible. We need to keep that in mind in life. It feels good to be making this kind of work again.